Ecuador looks to its own people in the battle against climate change

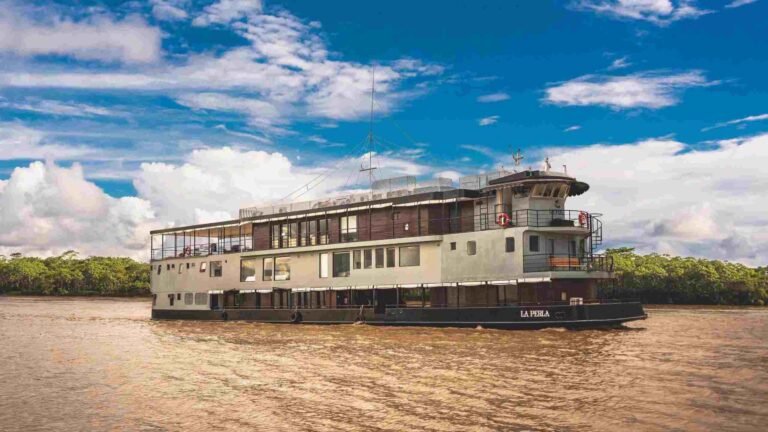

Ecuador’s Yasuni park where, as part of the climate change battle, oil will be left in the ground if donors pay half its value. Photograph: Dolores Ochoa/AP

We left thirsty Peru and have reached Quito in Ecuador on the great Oxfam/Guardian Andean climate journey. First stop is to meet the government and community leaders of a state that stretches from the Pacific coast, over the mountains, and deep into the Amazon forest. The environment minister is the redoubtable, who is grappling with the contradictions of having a revolutionary new constitution that guarantees the rights of nature and all living entities, yet depends on vast oil reserves. She is adamant that Ecuador wants to find ways to get out of the petrol economy and invest in renewables to avoid climate change. One plan is to guarantee to leave nearly one billion barrels of oil – nearly 20% of the country’s reserves – in the ground if rich countries and individuals give them $3.6bn, half the oil’s value.

The money from the Yasuni project would go to a UN-run fund to pay for national park conservation, as well as health and education. It would save nearly 400m tonnes of emissions and is being hailed as an innovative climate change solution.Hmmm. No one knows if this will catch on – even as we meet the minister, the press is reporting that the plan’s biggest western backer, Germany, is having second thoughts – but the radical government led by Rafael Correa will push it at the global climate change talks in Mexico in November.(Less remarkable, but something I have never seen before in 20 years of interviewing politicians, is the way Espinoza gets a senior civil servant to hold, brush and lovingly arrange her long brown hair throughout the hour-long interview. It’s a cross between a hairdresing salon and a Vanity Fair photo-shoot.)

The leaders of the country’s powerful, 12 million-strong indigenous peoples are also image conscious. Delfin Tenesaca, who runs the largest group, Ecuarunari, gives us an audience in front of a giant scarlet banner proclaiming human, water and other rights. The group sees climate change as an urgent social issue that can only be addressed by communities organising themselves.Even though Ecuador is right on the equator and is somewhat protected from climate change by the vast Amazon rainforest, its glaciers are melting fast and rainfall is decreasing steadily.

For the indigenous peoples, the “Pachamama” – or Mother Earth – is ill. We are going through a period of “vaciacad”, or melancholy, and we need to embrace “Sumak Kawsay”, the good way of living to restire Mother Earth’s balance, says Tenesaca.Interpreted, that means the world must abandon the neo-liberal policies that favour the rich. It must redistribute land, make the right to water universal and protect biodiversity. Any other way guarantees climate change, poverty and inequality.But the indigenous peoples’ relationship with government is complex. The new constitution gives them far more than what they had before, but they bitterly complain that the state has not passed the laws needed to make the constitution workable.Indigenous peoples throughout Latin America are gaining confidence. They are at the forefront of the new political philosophies emerging from Bolivia to Venezuela.

For the indigenous peoples, the “Pachamama” – or Mother Earth – is ill. We are going through a period of “vaciacad”, or melancholy, and we need to embrace “Sumak Kawsay”, the good way of living to restire Mother Earth’s balance, says Tenesaca.Interpreted, that means the world must abandon the neo-liberal policies that favour the rich. It must redistribute land, make the right to water universal and protect biodiversity. Any other way guarantees climate change, poverty and inequality.But the indigenous peoples’ relationship with government is complex. The new constitution gives them far more than what they had before, but they bitterly complain that the state has not passed the laws needed to make the constitution workable.Indigenous peoples throughout Latin America are gaining confidence. They are at the forefront of the new political philosophies emerging from Bolivia to Venezuela.

Climate change – specifically the right to water – is central to the political revolution taking place.One of the architects of the Ecuadorean constitition is Humerto Cholango, the man tipped to lead all Andean indigenous peoples.This intellectual onion grower, a friend of Bolivia’s radical president Evo Morales, shares four hectares with his eight brothers on the slopes of the ice-capped volcano Coyambe. He has led a remarkable struggle to protect and provide water for thousands of small farmers.They have, by consensus and without the help of the central or local state, redistributed land and water, conserved the high pastures of the mountain (which acts as a giant sponge), increased water supply by 10%, and repaired thousands of miles of water channel. It is a model of “Sumak Kawsay”. If this had been a World Bank project, it would have cost billions and probably would not have succeeded.What is impressive is that the indigenous peoples of Ecuador are proactive in adapting society to climate change. Government now gets its ideas from them.

Source: guardian uk

Leave a Comment